Hitting The Highline With Derek Hynd

A little over a year ago today, Derek Hynd graced New York with his presence. For such an occasion, we asked journalist/writer/filmmaker/surfer/close friend of Hynd's, Jamie Brisick, to lead a public discussion with the legend. The Pilgrim family gathered 'round to hear Hynd's incredible stories, and finally now, for those of you who couldn't make it and for those who want to let their minds wander back, we've revisited that night through the written word.

Presented here are a few highlights from Hynd's discussion with Jamie, from his years surfing, coaching, and shaping -- standing out, as always, as an experimental pioneer.

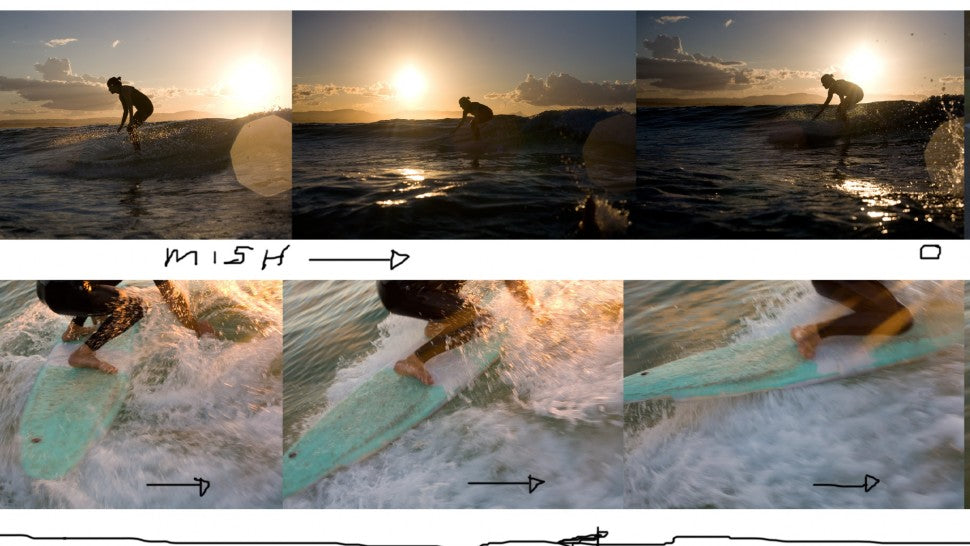

[Derek Hynd highline riding featured Litmus. Courtesy of Andrew Kidman.]

Jamie Brisick: We met in 1986, I think it was my first trip to Australia, but I knew of Derek long before this because Derek wrote in a magazine called Surfing World. Growing up in Southern California, Surfing World was a window into Australian surf culture. I hung on your words in a big way, and so it was an honor to meet you in 1986. At the time you were writing dispatches of the ASP tour, this was before the internet, so anything you wanted to know about the tour you got through Surfing World through Derek's stories. But you had a pro career before that.

Derek Hynd: Firstly, Nick Carroll is here tonight ladies and gentlemen, and we both started around about the same year at the same beach at Newport, with the same motives, career-based. And Nick got a more serious journalistic pursuit with Tracks, and I was doing bits and pieces with Surfing World. From the outset, there was a really interesting juxtaposition between Nick and I -- I had more free time than Nick did, which I think put me in a better stead to do the tour. By '86, the industry was already quite huge, and again, bringing Nick into the equation, he was with Surfing magazine and I was with Surfer magazine, so I definitely wasn't the only person putting words to life about the tour, but perhaps what happened was that I had a different scope on things having competed and coached. And on the competition side, that was really a quite short career, from '79 to '81. For whatever reason, things kind of stopped.

Jamie: Could you talk a little bit about your pro years? You were in the top ten at one point.

Derek: It was a quick rise and a bit of a sudden stop because I had an accident with a fin. Someone recently put it to me that, having not used a fin in seven years, maybe that's a delayed payback reaction for the fin ripping out my eyeball. But that's what happened in my career. My short time was bookended the year afterwards when I simply came back and got the results I wanted. And that was time enough for me probably.

[Portrait by Joe Falcone]

Jamie: You made the top ten with one eye.

Derek: Yeah, I mean it's all reflex. I'm sure people in the same situation have recovered in the same way.

Jamie: After making the top ten with one eye, you went on to become a coach and journalist on tour. You coached for Billabong, and you coached Mark Occhilupo during his big rise.

Derek: There are a lot of stories about pro surfing that could probably never be written, because it's on a plate and it happens really quickly, and there's not much education, even with kids out there today. Back in '84, sure there wasn't much money going around, but the idolatry that 17 year-old kids were faced with can lead to all sorts of downward spiral. That's what happened to Occ, and as his coach I --- I mean, he vanished. He vanished after winning an event in France and the next time I saw him, he turned up twenty pounds lighter, three weeks later. Twenty pounds lighter. He had a radical change in lifestyle at the hands of someone else in the top sixteen. That was the end of his surge, although he remained doing reasonably well in certain events, that was the end of him really until 1997, I think, at the Bells specialty event, the Super Skins.

Jamie: After witnessing so much pro surfing, what would be some of the highlights for you? What period?

Derek: Those months with Occhilupo, I'll never forget. Here was a kid, suddenly, who was better than anyone else had ever been before. I felt that point blank. I've seen Curren's rise, Cheyne Horan's rise -- and what was going on with Rusty surfboards, Occy piloting it was something to really behold. It kept on climbing with such momentum that he defeated Tom Curren four straight in the round of sixteen. It blew people's minds over the early part of the new season, to the point that Occy was regarded as the definite coming Messiah, and I believe he would have won the world title by a record margin, to this day maybe. But that was the best moment that I've come across, just those few months seeing the impossible suddenly possible.

[Derek Hynd wave riding. Courtesy of Andrew Kidman.]

Jamie: So I had a very lukewarm run as a pro surfer, but in about 1987 you became my coach because I was sponsored by Rip Curl and you were the Rip Curl team coach. And what I remember very vividly were the notebooks that you kept. You had your own sort of scoring system and every single maneuver was written blow-by-blow, almost like a horse race.

Derek: That's right. Every turn, every paddle, every master stroke, with a rating after every wave and comments at the end of it. It was logical with Surfer magazine for me to begin an analysis at the beginning of every new year, based upon reviewing all my notes. And unfortunately, my opinions were regarded by several pro surfers as shallow. But they didn't realize the depth that was in that actual analysis. I mean, probably 100,000 words a year just in doing notes, heap by heap.

Jamie: In 1992 you started The Search.

Derek: Yes, indeed. But as in many campaigns for companies, they bought out of desperation. And Rip Curl was really having a lot of trouble at the time. It never would have happened unless the main bank that was basically holding all the tickets on them hadn't given them an ultimatum to do something or face the consequences. With The Search campaign, for those who don't know, it was a vehicle to get Tom Curren traveling, because he had never been on a surf trip before in his life except to try and find his old man down in Costa Rica. The way it played out: Imagine the company's in a lot of bother, and there's a big board room table and all the underlings are seated around, it's a scene out of some English comedy show. Two of the heavy dudes who can make or break careers, Doug Warbrick and Brian Singer, are standing there and they just look down at us and go, "Right, you're all being paid to do I don't know what, but now you've really got to do something. We're in trouble and we need a campaign." And this is completely cold cocked, so there are a few mumbles of "how about this" and "how about that" and then I finally said, how about Curren goes on the road and surfs these waves and whatnot. And to cut a long story short, Sing Ding who makes life calls in a split second, much in the same way as Alan Green of Quiksilver, and is mostly always correct, said, "Well that sounds alright. What're you going to call it?" I could feel the looks of my coworkers, going "ha ha Hynd, here's where you fall apart" and just out of thin air I said, "Well, it's the search." And I barely knew what I said when suddenly Singer has just screamed around at everyone at the table, "See! I told you bastards you've gotta do something to earn your money!" and then pulled out a poster from behind himself that said "The Search" -- and it was Glenn Plake the extreme skier from five years before with tiny little writing that people had forgotten about. And I just thought, well, what a jag of all jags.

Jamie: But the jag turned out to be something really fantastic.

Derek: Yeah, it was only meant to be an 18 month campaign, but I guess it saved the company. Singer had the idea for The Search, but it wasn't meant to involve Tom Curren. It was meant to repeat what those guys, Doug Warbirck and Brian Singer, and Alan Green as well, did when Rip Curl first started. What they did when they first started the company was a response to the Bells Beach Surf Classic having all the famous Sydney and Queensland surfers come down and basically steal their waves and their women, and they didn't like that. It was an annual occurrence, so they got together the festering plan to head north selling product and do the same back to them.

So Singer thought, let's repeat what we did, which was finish work every Friday, get blotto traveling up the coast, find the women, come back, and talk about it on Monday morning -- and then do it all over again on Friday. That was meant to be the original Search. The campaign itself would have not happened if it weren't for Ted Grambeau, a great photographer, on the Canary Islands waiting for Tom Curren to show up, (of course he was a week late). And the mother of all swells landed at La Santa, which was a massive right hander peeling down the reef. The photo is with a tiny little figure of a surfer in the foreground in the distance, and it was too good of a shot to pass up -- hence the exotic waves, and that's how it started really.

[Backlit Derek Hynd. Courtesy of Andrew Kidman.]

Jamie: Talk a little bit about Jeffreys Bay, you built a house there.

Derek: It was a curved rock wall imitating what was then an 8th century Scottish fort, basically about a meter thick. Kind of an early gothic marriage with post modernism. It was closed off in the back and completely open in the front.

Jamie: And it had a slide in it -- a slide in your bedroom.

Derek: Yes, it did. The slide ended up being 88 degrees, and it's 20 feet up.

Jamie: So having this house at Jeffreys Bay, one of the finest waves in the world, you were able to do a lot of board experimentation.

Derek: It wasn't as much as experimentation as it was respect for the surfers who'd come before, and the designs they'd had obviously worked. Again, through other people, nothing is original in surfing, plenty of people had been looking at the potential of experimentation with older measurements of boards. But at any rate, just through a network of knowing people, I had built up a quiver of single fin boards. A couple of Tom Parrish's which mattered because they worked really well. I guess when you get to a certain level of surfing, revisiting the areas of what was really going through surfers' heads and their ability to control the board in certain situations, it was a challenge. With the Parrish board, there was one wave where it was probably eight foot outside going at six feet through Impossibles, and when that connects it tends to double up. Where the knowledge of what they must've been doing, maybe not Lopez, but say Rory Russell, just in reverse, the drive off the bottom, then not exactly a side slip but letting the board drift backwards over the fun bowl and then grip, and then sit there, not at a high speed but at enough speed where it could go straight through. Before that wave I really didn't know what I was doing, and I don't think after that wave I surfed the board much more because it was done. And as far as Litmus went, those guys simply turned up and I happened to be there, there was no major plan.

Jamie: So in the early 1980's a fin takes one of your eyes out, and for the last seven years you've been surfing finless.

Derek: There's several reasons why it started, one being a girlfriend at the time, and one being the Daytona 500. I was over there and I saw the leading car at 200 miles an hour hit the speed bank and then lose it, but then in losing it, it did a drift across the top before it went end over end. And at least by appearances it looked to pick up speed. And that got me thinking, what might happen if you could get a board in that position on the right wave? Would it pick up speed? The other thing is boredom. It's not about getting old, it's about knowing your potential, and what could've happened in the past but didn't. I always felt a great affinity with Buttons Kaluhiokalani and Mark Liddell. These guys were really adventurous Hawaiian surfers, and Larry Bertlemann's mold, but were doing things that I believe that judges just didn't understand in the late 1970's. They didn't find a place in professional surfing because of it. Even though they were massive in Japan, and did a lot to bring that Japanese boom into fruition, their fins were moving further up the board and getting smaller as the '70s wore on, and I got the feeling, years later, that Slater came more from Mark Liddell and Dane than he did from anyone else. If those guys had been left to their own devices with the arena to showcase, perhaps they would've found themselves with very minimal fin equipment.

Then there's aspects of fun, it's gotta be fun. When you take off at Jeffreys Bay and it's a phenomenal wave, and you're certain about what's going to happen, then that's not a good thing. You want it to be completely uncertain about what's going to happen. But it had been interesting going from small beach breaks to serious waves having learnt through pure experimentation what can and can't be done. Even though anyone else who shared the same desire could go completely different routes and reach the same outcome because there would be fifty different permutations for every board. It's just that I've basically used two and just worked them as much as I can. The first one worked at beach breaks, and then it didn't work at Jeffreys, and the second one with hard rail edges does work at Jeffreys and adapted to small surf. It's a progression, at least it feels like a progression. And in the surfing space, it's such a conservative world now, it's great to climb out of the box.

[Derek Hynd courtesy of Andrew Kidman.]

Audience question: Can you talk about the moment when Tom Curren took the Skip Frye fish out at Jeffreys Bay? What were the circumstances leading up to it and what were people's reactions?

Derek: I visited Skip about four months before, and wanted to get a handle on where the guys from New Break at Sunset Cliffs had come from, and what they were actually doing out there because I had surfed it once or twice and I had seen the line that they were drawing had a lot of speed and a highline. Knowing that Skip had blown out the locals for many years, by in the course of a day, going from 10'6" to say 5'10". So he was conquering his age by just thriving on this particular board. I said build it without any rail curve as you normally would. So it was 5'10" and I wanted to take it to Jeffreys to see what would happen. I rode one surf on it and couldn't turn it. And I put it in the rack, and I can't exactly remember how many months later it was that Curren arrived, but the surf wasn't that good, but Albatross, at the very bottom, was firing. I walked all the way down and Tom was going through a phase where he did not have a designated board from anyone, so I gave it to him, just because I knew that in his legs he was a very powerful surfer. And Sonny Miller filmed that first session, wave for wave, and it was the first time he'd ever ridden the board. Those round house cutbacks are quite legendary now. But unfortunately he never picked up a fish again. That was it. Given where he came from with Al's shapes, they weren't that far removed, he could've revisited a lot of stuff. Maybe he still could.

Derek: My probable greatest surfing moment was getting sprayed in the face by Michael Peterson at Express Point in '77. I was paddling out for my quarter finals, just a kook, somehow I had made the quarter finals in six man heats. And he rode the last wave, I could see it happening from about a hundred yards away. He's timed his first turn, he's going to do this, and maybe, just maybe, I'll be paddling over the top. And it happened. The jitter bug turn and just the whoooosh -- and as he went past, I thought, well, I've been sprayed by Michael Peterson.

[Portraits courtesy of Joe Falcone]

Scenes from that night: